Introduction

Last updated on 2025-06-05 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What are virtual machines and containers?

- How are they used in open science?

Objectives

- Explain the main components of a virtual machine and a container and list the major differences between them

- Explain at a conceptual level how these tools can be used in research workflows to enable open and reproducible research

Introduction

You might have heard of containers and virtual machines in various contexts. For example, you might have heard of ‘containerizing’ an application, running an application in ‘Docker’, ‘spinning up’ a virtual machine in order to run a certain program.

This lesson is intended to provide a hands-on primer to both virtual machines and containers. We will begin with a conceptual overview. We will follow it by hands-on explorations of two tools: VirtualBox and Docker.

If you forget what a particular term means, refer to the Glossary.

This lesson assumes no prior experience with containers or virtual machines. However, it does assume basic knowledge about computer and networking concepts. These include

- Ability to install software (and obtaining elevated/administrative rights to do so),

- Basic knowledge of the components of a computer and what they do (CPU, network, storage)

- Knowledge of how to navigate your computer’s directory structure (either graphically or via the command line).

Prior exposure to using command line tools is useful but not required.

What are virtual machines and what do they do?

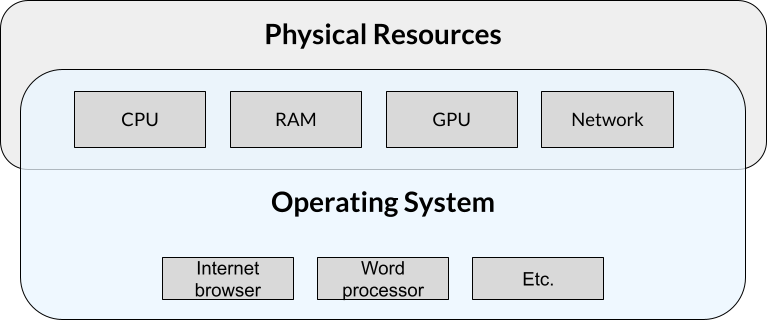

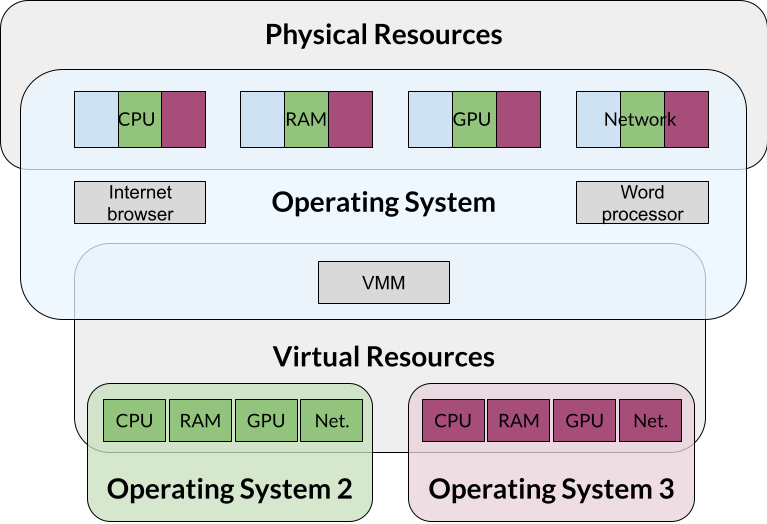

Normally, computers run a single operating system with a single set of applications. Sometimes (for reasons we’ll discuss soon), people might want to run a totally separate operating system with a different set of applications. One way to do that is to split up the physical resources like CPU, RAM, etc. and present them to that second operating system for its exclusive use. The concept of splitting up these resources (i.e., virtualizing them) so that only this second operating system can access them is the idea behind a virtual machine.

At its core, a virtual machine (referred to as VM from now on) is a self-contained set of operating system, applications, and any other needed files that run on a host machine. The VM files are usually encapsulated inside of a inside single file called a VM image. The file you downloaded during the lesson setup is an example of an image.

One way to think of the VM concept is a computer that runs inside your computer. All the programs that run inside this mini computer can’t “see” anything running outside of it, either in the host or other VMs running on the same physical computer.

Why would we want to run a mini computer inside of our main computer? VMs are commonly used to

- More easily manage and deploy complex applications.

- Run multiple operating systems and their applications on the same physical hardware.

Examples:

- Your bank’s internal systems need to be robust against risks like hardware failure, hacking, weather events, etc. One way to achieve this is to run several identical servers spread out geographically. While one could install all the software on each server, using a VM reduces complexity by allowing the same software and associated configurations to be quickly deployed and managed across varying hardware.

- Many cloud computing providers like Amazon allow users to purchase resources on their systems. To maximize their investment on physical hardware, these companies will set up a virtual server for each customer. Functionally, these virtual servers behave as a standalone machine but in reality, there may be dozens of other virtual servers running on the same physical system.

VMs are also commonly used in academic research scenarios as well as they can help with the problem of research reproducibility by packaging all data and code together so that others can easily re-run the same analysis while avoiding the issue of having to install and configure the environment in the same way as the original researcher. They also help optimize the usage of the computing resources owned by the institution. You might have interacted with VMs at your institution if you’ve ever logged into a “remote desktop” or “virtual computing environment” that many institutions use to provide access to licensed software. Some Carpentries workshops also use VMs as part of their curriculum.

Benefits of VMs

- Help with distributing and managing applications by including all needed dependencies and configurations.

- Increase security by isolating applications from each other.

- Maximize the use of physical hardware resources by running multiple isolated operating systems at the same time.

What are containers and what do they do?

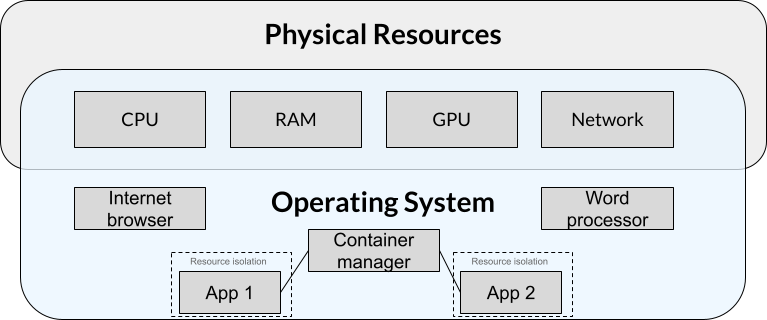

Containers are conceptually similar to VMs in that they also encapsulate applications and their dependencies into packages that can be easily distributed and run on different physical machines. A notable difference is that when using containers, hardware is not virtualized and containerized applications must be compatible with the host OS and its hardware. In more technical terms, applications running in a container share the host’s kernel and therefore must be compatible with the host’s architecture. In practical terms, this means that containers:

- Are generally less resource-intensive than comparable VMs, at the cost of portability.

- Are generally not able to run applications written for one operating system on another.

Two core concepts

Ephemerality

Containers should be considered ephemeral so that they can be destroyed and recreated at any time such that the application within simply resumes as if nothing had happened. Therefore, containerzied applications must be designed in such a way that allows the container manager to save all user data and configurations outside of the container. This separation is what enables some of the use cases below.

Modularization A popular paradigm is modularizing a complex application into smaller, loosely connected components called “microservices”. Each microservice runs in its own container and communicates with other microservices via an isolated, private network that is set up by the container management platform. This approach helps with maintenance, scalability, and robustness since a microservice can be stopped, updated, and/or swapped without affecting the other microservices.

Examples

- Web applications. E.g., a web front-end container that talks to a database backend running in a different container. In this case, the ephemerality and microservice concepts allow for easily updating the software, while being sure that the data won’t be affected. For example, the database can be updated or replaced without needing to touch the front-end software at all (thereby allowing error or maintenance messages to function).

- Data science, data management, and other research uses. In these applications, the benefits of ephemerality and modularization via microservices are realized to enable reuseable, reproducible, and cloud-native workflows. Due to their lighter weight and the ability to define and create containers via plain-text blueprints (e.g., Dockerfiles – more on that later), containers have become more popular than virtual machines in research environments.

Benefits of containers

- A lighter footprint (mainly around lower CPU and memory requirements) compared to VMs.

- Quickly and easily maintain a complex application without affecting any user data or causing issues with conflicting dependencies in the host OS.

- Quickly and easily scale applications. For example, when there is a need to dynamically run multiple instances of an application across a cluster of servers to handle increased demand.

- Robustness of an application stack. If an application is made up of smaller applications that talk to each other via standard mechanisms (e.g., web APIs), it is easier to pinpoint and recover from problems.

Comparing virtual machines and containers

| Virtual Machines | Containers | |

|---|---|---|

| Contains all the dependencies needed to run an application | Yes | Yes |

| Isolates an application from the host OS | Yes | Yes |

| Ease of distribution | Very easy | Easy/hard (depending on complexity and hardware compatibility) |

| Disk space, CPU, and memory requirements | Larger | Smaller |

| Presents virtual versions of real hardware like CPUs, disks, etc | Yes | No |

| Scaling based on computing needs | More difficult | Easier |

| Able to run applications from one operating system on another | Yes | Sometimes* |

| Able to run applications from one CPU architecture on another | No** | No |

* It’s possible in some cases. For example, Docker on Windows can run Linux containers because it secretly runs them inside a Linux VM.

** It is possible with some software and with some architectures. In the background, the software uses emulation which is different on a technical level than virtualization. Examples of architectures are Intel x86 (32 bit or 64 bit), ARM, RISC and more.

Challenge 1:

If you are running a web browser inside a VM, would the host OS able to determine what internet addresses you are connecting to?

What about an application making web requests from inside a container? Can the host see the IP addresses your containerized application is connecting to?

In both cases, the host can (in principle) see what sites or IP addresses the guest OS or container is connecting to. In the VM case, even though the network hardware is virtualized, the actual data still has to go through the real hardware at some point. For containers, the container already uses the real hardware the effect is the same. If virtual private network (VPN) software is used within the container or VM, then the only thing the host could see is the address of the VPN.

- Conceptually, a virtual machine is a separate computer that runs with its own resources, operating system, and applications inside of a host operating system.

- Containers are like lightweight virtual machines with some subtle but consequential differences.

- Containers and virtual machines can address many of the same use cases.

- Both virtual machines and containers are commonly used in academic research but containers are more popular.